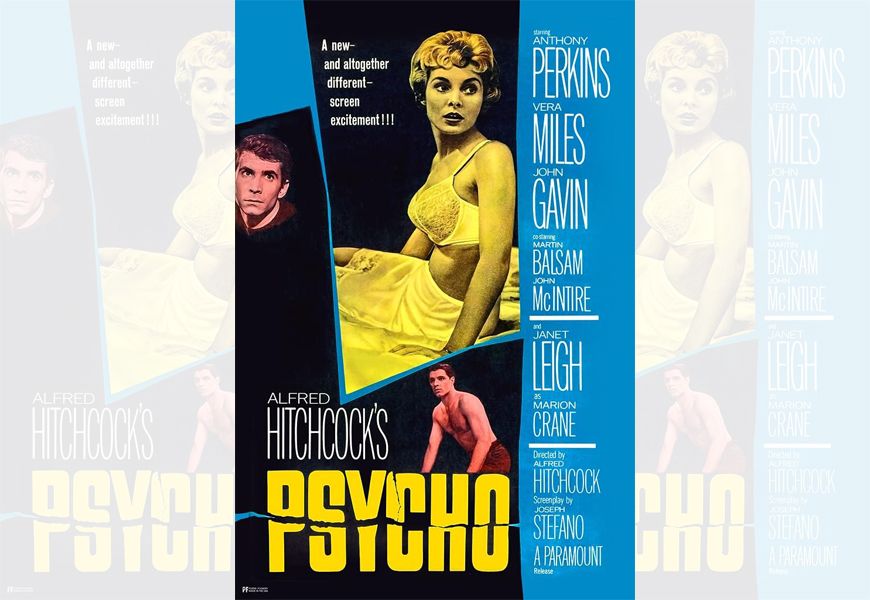

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho didn’t just terrify audiences — it reinvented cinema itself. From its shocking storytelling to its radical editing and taboo-breaking themes, the 1960 thriller changed the way movies are made, watched, and feared…

When Psycho first hit theatres in June 1960, audiences weren’t just watching another Alfred Hitchcock thriller—they were watching the rules of cinema being rewritten in real time. The film that began with a woman on the run and ended in a dimly lit basement didn’t just terrify—it transformed how stories could be told, how violence could be seen, and how audiences could be shocked. More than six decades later, Psycho still ripples through every psychological thriller, slasher, and twist-driven narrative that followed.

Today Psycho is considered one of Hitchcock’s best films, and is arguably his most famous and influential work. But, the directly didn’t simply craft a horror film with Psycho — he fractured Hollywood’s old rules. Sixty-five years later, its influence still echoes in every twist, scream, and psychological thriller that followed.

The shock that split Hollywood in two

By the late 1950s, Hitchcock was already a household name. He was “The Master of Suspense,” known for sleek, stylish thrillers like Rear Window (1954) and North by Northwest (1959). But Psycho was different. Shot in black and white, on a modest budget, using the crew from his television show Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the film looked more like an experiment than a studio prestige picture. Paramount Pictures even refused to finance it at first, calling the story “repulsive.”

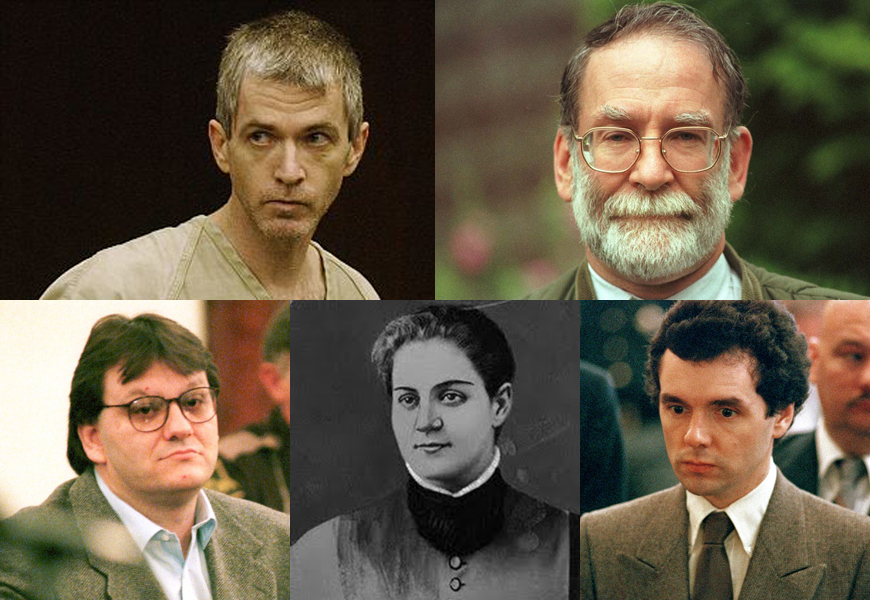

Yet that was exactly Hitchcock’s point. Adapted from Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel (loosely inspired by real-life murderer Ed Gein), Psycho was designed to break Hollywood’s polished façade. Hitchcock wanted to bring horror out of the shadows and into the ordinary world—to make audiences afraid not of monsters, but of people.

And then came that scene.

The shower scene—78 camera setups, 52 cuts, and less than a minute of screen time—changed cinema forever. It was graphic without showing much, visceral without gore, and revolutionary in its editing. The stabbing of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) was an act of cinematic sleight of hand, made horrifying by suggestion, sound, and rhythm. Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking violins became as iconic as the image itself, creating a language of psychological horror that filmmakers still borrow today.

The death of the leading lady

Perhaps the most daring choice Hitchcock made wasn’t visual—it was narrative. For 40 minutes, audiences believed Psycho was Marion Crane’s story. She was the flawed heroine, on the run with stolen money, seeking redemption. And then, suddenly, she was gone.

To kill off a major star like Janet Leigh—halfway through the film—was unheard of. It shattered expectations and redefined the idea of the “safe” protagonist. Hitchcock upended the contract between audience and storyteller: anyone could die, and anything could happen.

This wasn’t just a twist—it was a statement. It forced viewers to confront their voyeurism, their desire to watch, their complicity in the spectacle of violence. The shower scene became a mirror, reflecting the audience’s own fascination with transgression.

Filmmakers from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino, from Wes Craven to Jordan Peele, have cited Psycho as a turning point. It marked the moment when cinema started asking deeper, darker questions about its own moral boundaries.

The birth of the modern horror film

Before Psycho, horror movies were gothic and otherworldly—haunted castles, fog, vampires, monsters. Psycho dragged horror into daylight, into a shabby roadside motel. The terror was no longer supernatural; it was psychological, intimate, domestic. Norman Bates wasn’t a creature from the crypt—he was a boy next door with mother issues.

This shift gave rise to a new kind of horror: one rooted in realism, sexuality, and mental instability. Psycho is often credited as the blueprint for the modern slasher film. Without it, there would be no Halloween (John Carpenter even cast Janet Leigh’s daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis, as a nod to Hitchcock’s influence), no Friday the 13th, no Scream.

But it wasn’t just horror that evolved. The psychological thriller, as a genre, was born. Films like Silence of the Lambs, Seven, and Gone Girl all trace their DNA back to Psycho’s unsettling blend of violence and voyeurism, morality and madness.

Breaking the rules of storytelling—and of Hollywood

When Hitchcock released Psycho, he didn’t just direct a film; he staged an event. He famously insisted that no one be admitted to the theatre after the film began—a revolutionary marketing move that built suspense and transformed the moviegoing experience into a shared ritual. Posters warned audiences: “No one… BUT NO ONE… will be admitted after the start of each performance!”

It worked. Lines wrapped around city blocks. Viewers fainted, screamed, ran from theatres. For the first time, a movie became a timed, communal experience—something that had to be seen, not just watched. Hitchcock turned film into an event, paving the way for the blockbuster era decades later.

He also challenged the censorship system. The Motion Picture Production Code (known as the Hays Code) was still in effect, dictating what could be shown on screen. Yet Psycho depicted unmarried lovers in bed, a flushing toilet, and hinted at sexual deviance—scandalous in 1960. Hitchcock pushed against the limits until they cracked, and by doing so, helped usher in the freer, more daring filmmaking of the 1960s and ’70s.

Norman Bates and the psychology of fear

Anthony Perkins’ portrayal of Norman Bates remains one of the most complex performances in film history. Sweet, boyish, awkward—Norman made evil look normal. Hitchcock used him to blur the lines between innocence and guilt, sanity and madness.

The film’s final reveal—that Norman had been impersonating his dead mother—wasn’t just shocking; it was symbolic. It reflected a growing cultural fascination with psychology, Freudian theory, and the dark recesses of the human mind.

Before Psycho, villains were external forces. After Psycho, they lived inside us. The real horror was the psyche itself.

How Psycho echoes through film today

Every time a director uses quick cuts to simulate chaos, every time a film kills off a main character early, every time a story asks us to empathize with the killer—Psycho is there.

Gus Van Sant’s 1998 shot-for-shot remake proved that the original’s power wasn’t just in its plot—it was in its timing, tone, and tension. Filmmakers from Brian De Palma (Dressed to Kill) to Darren Aronofsky (Requiem For A Dream and Black Swan) have built entire oeuvres on Hitchcock’s psychological groundwork. Even series like Bates Motel and American Psycho owe their existence to the film’s eerie exploration of identity and repression.

More subtly, Psycho changed how we watch movies. It trained audiences to expect twists, to question the reliability of what they see, to anticipate the knife behind the curtain. In that sense, Hitchcock didn’t just invent modern horror—he invented modern spectatorship.

The curtain never closed

In the final moments of Psycho, Norman sits in a police cell, smiling faintly as “Mother’s” voice whispers in his head: “She wouldn’t even harm a fly.” The camera lingers, and for a moment, you realize the monster has won—not through violence, but through our attention.

That’s Hitchcock’s ultimate trick. He didn’t just scare us—he implicated us. He made us realize that the urge to look, to peek behind the shower curtain, is what keeps movies alive.

Psycho didn’t merely change the rules of cinema; it changed the psychology of watching itself. The shockwaves it sent through Hollywood are still being felt every time a filmmaker dares to surprise, unsettle, or turn a mirror on the audience.

In the end, Psycho isn’t just a movie about madness—it’s about obsession. Hitchcock’s, Norman’s, and, ultimately, ours.

RELATED: