By Christopher Turner

On a frigid winter morning in February 1965, thousands of Canadians gathered on Parliament Hill in Ottawa to witness the lowering of one flag and the raising of another. The Canadian Red Ensign—a crimson banner adorned with the Union Jack and Canada’s coat of arms—was solemnly folded and carried away. In its place, unfurled against the grey Ottawa sky, came something entirely new: a stark, modern design of a single red maple leaf on a field of white, flanked by two bold red bars.

It was clean, contemporary, and unmistakably Canadian. Yet it was also deeply controversial. In fact, the debates leading up to that moment had nearly fractured Parliament. For some, the change was a betrayal of heritage, while for others, it was the long-awaited birth of a truly national identity.

Six decades later, Canada’s simple flag feels inevitable, woven into everything from Olympic uniforms to airport lounges, stitched onto denim jackets and tattooed on skin. But the story of how Canada arrived at this emblem is not simply one of design. It is the story of a country’s struggle to define itself—between empire and independence, between French and English, between past and future.

Here’s the history of the national flag of Canada, popularly referred to as the Maple Leaf.

Before the leaf: early symbols of a colony

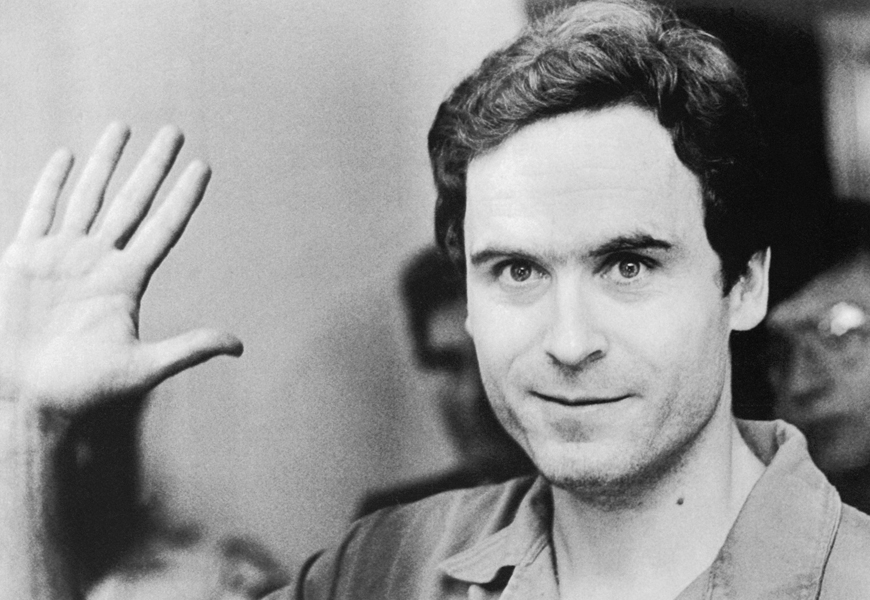

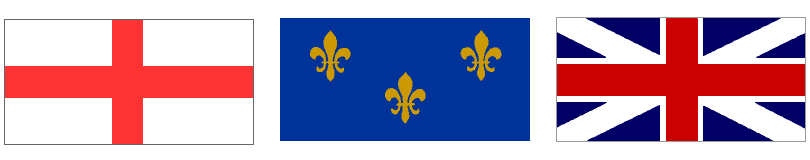

Canada’s earliest flags were not Canadian at all.… Early explorers planted symbols of European monarchy in Indigenous lands when they arrived. When Italian navigator and explorer John Cabot reached what was later named Newfoundland in 1497, he carried The Saint George’s Cross, which would later evolve into the national flag of England; in 1534, French maritime explorer Jacques Cartier planted a cross in Gaspé bearing the French royal coat of arms with the fleurs-de-lis. The British national flag, the Union Flag (commonly known as the “Union Jack”) became a common sight across much of the country from the time of British settlement in Nova Scotia after 1621. Then, after 1763, when Britain claimed control over New France, the Union Jack became the dominant banner from coast to coast, fluttering above forts, schools and all government houses.

By Confederation in 1867, Canada had its own government and parliament, and a growing national consciousness—but no official flag. In practice, the Union Jack still reigned. But Canadians also turned to another symbol: the Red Ensign, a British naval flag with Canada’s evolving coats of arms added to it.

The Red Ensign with the addition of the Canadian composite shield was first flown in 1870 and was unofficially used on both land and sea. The flag changed subtly several times through the years; as new provinces joined Confederation, their arms were added to the shield. At first unofficial, the Red Ensign slowly gained traction and, finally, in 1892, the British admiralty approved the use of the Red Ensign for Canadian use at sea. In the years that followed, Canadian troops marched under it during the Boer War (1899–1902), World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). For soldiers in muddy trenches or on storm-tossed ships, the Red Ensign became a rallying point, and when survivors returned home, they carried deep loyalty to it.

The evolving Canadian Red Ensign was respected, but there were early movements to ensure Canada had a true representation of the country. In 1925, then Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King established a committee to design a flag that could be used at home, but it was dissolved before the final report could be delivered. Despite the committee’s failure to produce a flag, public sentiment in the 1920s was widely in favour of fixing the flag “problem” for Canada, and so new designs were proposed in 1927, 1931 and 1939. However, it would be decades before a flag was finalized.

The rise of the maple leaf

The maple leaf had been associated with Canada long before it became the focal point of the national flag. In 1834, the newly founded Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Montreal adopted it as a symbol of French Canadian identity. By the 1860s, it appeared on Canadian regimental insignia, on coins and in popular songs such as Alexander Muir’s “The Maple Leaf Forever” (1867), which celebrated Confederation.

Unlike the Union Jack or Red Ensign, the maple leaf was organic, local and distinctly North American. It grew in Canadian forests, turned fiery red each autumn, and could belong equally to English, French and immigrant communities. By the mid-20th century, it was clear that the leaf had taken root in the national imagination—it simply hadn’t found its definitive form…yet.

By the 1950s and ’60s, Canada was maturing as a nation, yet it still lacked a distinct flag. To many, continuing to fly the Red Ensign symbolized a colonial hangover.

The call for change gained urgency under Nobel Peace Prize-winning diplomat Lester B. Pearson. In 1960, Pearson, then Leader of the Opposition, declared that he was determined to solve what he called “the flag problem.” Pearson envisioned Canada as a peacekeeping, bilingual, multicultural country, and to him, this issue was critical to defining Canada as a unified, independent country. When Pearson was elected the 14th prime minister of Canada in 1963, he promised to resolve the question of a new national flag in time for Canada’s centennial celebrations in 1967.

“I believe that a flag designed around the maple leaf,” Pearson famously declared, “would be a banner under which all Canadians could serve, at home and abroad, and be a symbol of the unity of the nation.”

Pearson’s plan was not universally admired. His proposal sparked a firestorm known as “The Great Flag Debate.”

The Great Flag Debate of 1964

When Pearson introduced the idea of a new flag in Parliament in June 1964, opponents erupted. Veterans’ groups accused him of disrespecting soldiers who had fought under the Red Ensign through global conflicts. Conservatives claimed the move was unpatriotic and divisive. Many English Canadians, especially those with strong ties to Britain, feared the Union Jack would be erased from public life.

The debate soon turned into political theatre. Opposition leader (and former prime minister) John Diefenbaker of the Progressive Conservatives was particularly ferocious, insisting that the Red Ensign remain. He orchestrated marathon speeches and procedural delays, dragging out the conversation for months. Newspapers brimmed with letters to the editor—some demanding tradition be preserved, others pleading for a fresh start.

A steering committee was set up and Canadians across the country sent in thousands of designs and concepts. Some were earnest, others comical: beavers chewing branches, hockey sticks crossing like swords, and a multicoloured maple leaf that resembled a psychedelic tie-dye.

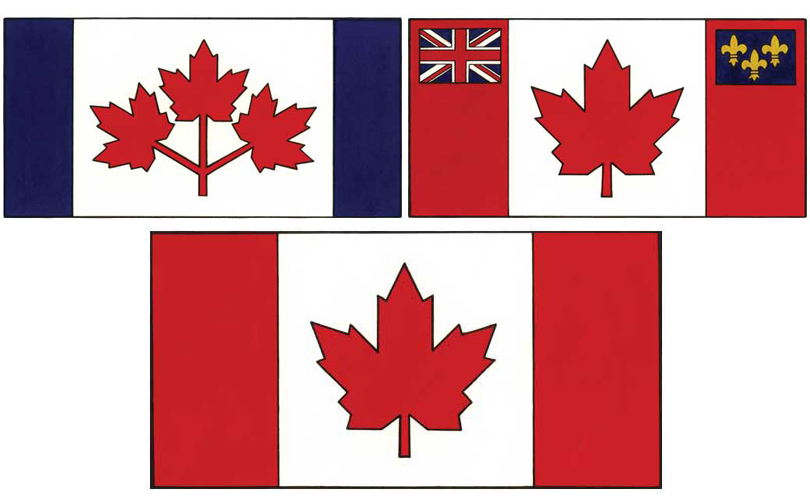

Ultimately, the search was narrowed to three contenders:

- Pearson’s favoured design—a blue-white-blue flag with three red maple leaves at its centre that was created by Alan Beddoe.

- A modified Red Ensign with the fleur-de-lis and the Union Jack.

- A simple red-white-red design with a single stylized 11-pointed maple leaf.

It was the third option, designed by historian George F. G. Stanley and Member of Parliament John Matheson, that triumphed. On October 22, 1964, the committee voted in favour of the single-leaf concept, stating that its minimalism, symmetry and clarity proved irresistible. As Matheson later reflected, the design “was simple, distinctive, and carried no baggage of the past.”

February 15, 1965: A flag is born

After the National Flag of Canada was approved by the House of Commons and the Senate in 1964, it was proclaimed by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on January 28, 1965. It was officially raised for the first time in an inauguration ceremony on Parliament Hill on February 15, 1965. The ceremony was solemn but celebratory. Governor General Georges Vanier, a decorated war hero, watched alongside Pearson and thousands of citizens.

As the Red Ensign came down, some veterans saluted with tears in their eyes. When the maple leaf ascended, cheers erupted. For the first time, Canada had a flag that was entirely its own.

Not everyone was convinced. Diefenbaker continued to fume, and in some communities the Red Ensign still flew defiantly for years. Yet gradually, the maple leaf won over hearts. It was clean, modern and instantly recognizable. It did not pit French against English, old against new—it simply was.

The flag’s symbolism

The Canadian flag is deceptively simple, but every element carries meaning:

Red and white: Declared Canada’s official colours in 1921 by King George V, they symbolize sacrifice and peace. Red also recalls Saint George’s Cross (England) and white the French royal emblem.

The Maple Leaf: With 11 points, the stylized leaf is not botanically precise but symbolically powerful—representing unity, resilience and the Canadian landscape.

The vertical bars: The two red bands are sometimes said to evoke the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, with Canada spanning between.

Its minimalist design set it apart in an era when many flags were cluttered with coats of arms and symbols. The maple leaf offered a modernist approach: bold, memorable and easy to reproduce—whether painted on a barn, stitched on a patch or waving from a pole.

From controversy to consensus

Over time, the maple leaf flag has transcended its contested origins. During the 1972 Summit Series, hockey fans waved it ecstatically after Paul Henderson’s historic goal against the Soviet Union. At the 1976 Montreal Olympics, it flew proudly as Canada hosted the world. By Expo 86 in Vancouver and the Calgary Olympics in 1988, it had become a cheerful shorthand for Canadian friendliness.

Abroad, the flag became a protective symbol. Canadian travellers famously sewed maple leaf patches on their backpacks, signalling politeness and neutrality in an often turbulent world. Peacekeepers carried it into international conflicts, lending the flag a reputation for diplomacy rather than aggression.

At home, the maple leaf was embraced by artists, fashion designers and activists. It appeared on T-shirts, beer cans and even haute couture. Designers like Dean and Dan Caten, the Canadian twins behind Dsquared2, the Italian luxury fashion house based in Milan, have reimagined it countless times, proving its versatility as both pop culture emblem and luxury icon.

In 1996, then Prime Minister Jean Chrétien declared February 15 the annual National Flag of Canada Day. Each year, ceremonies across the country mark the anniversary of the flag’s first raising. Schools host assemblies, veterans share their memories, and citizens reflect on how a once-contested symbol has come to represent unity.

A flag for a changing Canada

As Canada has evolved—embracing multiculturalism, Indigenous reconciliation and debates about national identity—the maple leaf has remained a canvas for reflection.

Some Indigenous leaders point out that the flag, like Confederation itself, did not originally reflect the First Peoples of the land. In recent years, flags incorporating Indigenous symbols have been flown alongside the maple leaf at official ceremonies, part of an ongoing conversation about representation and inclusion.

At the same time, the flag continues to serve as a unifying emblem during moments of triumph and tragedy. It was lowered across the country after 9/11, carried during Pride parades, and draped over the coffins of soldiers lost in Afghanistan. It has become a living, breathing emblem of a nation constantly redefining itself.

Today, the Canadian flag is one of the most recognizable national emblems in the world. A symbol that instantly communicates “Canada” without words, representing a delicate balance between history and progress. It is also a reminder that national symbols are never static—they are negotiated, fought over, and eventually embraced. It is a reminder to Canadians that their identity is not inherited but chosen, not imposed but created together.

Its journey from contested design to beloved emblem tells a deeper truth: Canada, like its flag, is always evolving, always negotiating its past and future. The maple leaf is not perfect, nor is it complete. But it is resilient. It is rooted. And it continues to grow.

The maple leaf has become more than a symbol—it is shorthand for the country itself. As historian George F. G. Stanley once said of the design: “A flag is not a mere ornament; it is a symbol of a nation’s identity, a banner of its destiny.”

For Canada, that destiny remains a living work of art—forever marked by the red maple leaf, fluttering in the wind.

![]()